DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic pathway for IBS

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends a positive diagnostic strategy as compared to a diagnostic strategy of exclusion for patients with symptoms of IBS.1 The ACG recommends against routine colonoscopy in patients with IBS symptoms younger than 45 years without warning signs.

IBS diagnostic pathway1-6

IBS is an affirmative, symptom-based diagnosis, NOT a diagnosis of exclusion.7

Recurrent abdominal pain associated with altered bowel movements

Elicit detailed history of symptoms, conduct abdominal/rectal exam, and order appropriate laboratory tests

See below for more information on patient assessment and diagnostic testing.

Are any alarm features present?

- Patient age >50 years

- Blood in stool

- Anemia

- Fever

- Unintentional weight loss

- Family history of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or colon cancer

- Nocturnal diarrhea

- Recent antibiotic use

- Travel history to regions with recognized diarrhea-related pathogens

- Abdominal mass or evidence of defecatory disorder

Does the patient meet Rome IV diagnostic criteria?

Recurrent abdominal pain ≥1 day per week, on average, associated with 2 or more of the following: (1) defecation; (2) a change in stool frequency; (3) a change in stool form

NO

Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months ago

NO

Affirmative IBS diagnosis

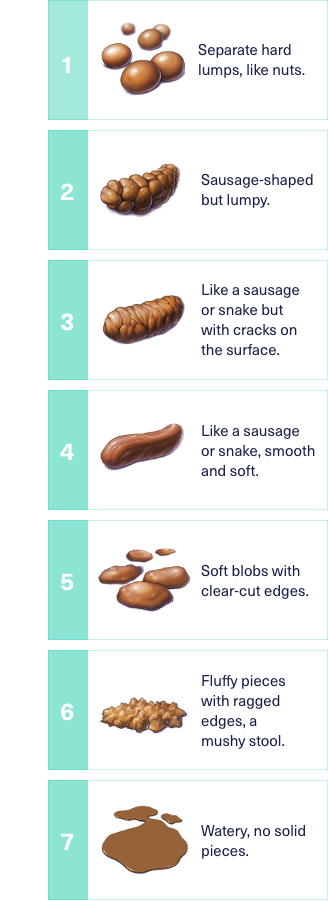

Evaluate stool consistency using the Bristol Stool Form Scale for IBS subtyping*

See below for more information on IBS subtyping.

IBS-Constipation (IBS-C)

Hard/lumpy stools >25%

IBS-Mixed (IBS-M)

Mixed-stool pattern

IBS-Diarrhea (IBS-D)

Loose/watery stools >25%

Consider alternative diagnoses

Perform additional investigations, as required

See below for more information on additional tests and differential diagnoses.

The Rome Foundation suggests for clinical practice, a diagnosis may be made with a lower symptom frequency and a shorter duration (8 weeks or more) than those required above, provided that symptoms are bothersome for the patient (i.e., interfering with daily activities/quality of life) and there is clinical confidence that other diagnoses have been sufficiently ruled out.7

Patient assessment1-6

Patient history

The following are important to consider when taking a history from a patient with possible symptoms of IBS:

- Predominant/most bothersome symptom

- Dietary habits and relationship of symptoms to food or stress

- Time course of the symptoms (chronicity)

- Other intestinal symptoms or conditions. Common co-existing disorders include dyspepsia and GERD

- Extraintestinal symptoms or conditions. Common co-existing conditions include fibromyalgia, fatigue, and migraine

- Psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., anxiety, depression)

- Family history, including history of abuse

Physical exam

Although a physical exam is normal in the majority of patients with IBS, a rectal and pelvic exam can serve to:

- Reassure the patient

- Exclude alternative diagnoses

- Identify pelvic floor dysfunction

Diagnostic evaluation and differential diagnosis1-6

What alarm features should I look for in patients with symptoms of IBS, and what might they mean?

| Alarm features | Potential differential diagnosis warranting further investigation |

|---|---|

| Anemia | Celiac disease, IBD, colon cancer |

| Family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disorder (IBD), or celiac disease | Celiac disease, IBD, colon cancer |

| Nocturnal diarrhea that awakens the patient | Colorectal cancer, IBD, microscopic colitis |

| Onset >50 years of age | Microscopic colitis, colon cancer |

| Recent antibiotic use | Clostridioides difficile colitis |

| Rectal bleeding | IBD, colon cancer, hemorrhoids, ischemic colitis |

| Unintentional weight loss (>10% of body weight) | IBD, celiac disease, colon cancer |

| Persistent frequent diarrhea without hematochezia | Bile acid malabsorption |

| Persistent bloating and diarrhea unresponsive to dietary interventions | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

Other possible diagnoses that may need to be considered based on a patient’s specific history and symptoms include:

- Chronic constipation†

- Narcotic bowel syndrome

- Abdominal wall pain

- Defecatory disorder

- Endometriosis

In the absence of alarm features, what diagnostic tests are available in order to diagnose IBS?1-8

In the absence of alarm features, extensive diagnostic testing is NOT required to diagnose IBS. Common diagnostic tests often performed in patients suspected of having IBS have a very low diagnostic yield.

Diagnostic testing in patients with symptoms of IBS

| We recommend that serologic testing be performed to rule out celiac disease in patients with IBS and diarrhea symptoms. Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence. | |

| We suggest that fecal calprotectin (or fecal lactoferrin) and C-reactive protein be checked in patients without alarm features and with suspected IBS and diarrhea symptoms to rule out inflammatory bowel disease. Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence for C-reactive protein and fecal calprotectin. Strong recommendation; very low quality of evidence for fecal lactoferrin. | |

| We suggest a positive diagnostic strategy as compared to a diagnostic strategy of exclusion for patients with symptoms of IBS to improve time to initiate appropriate therapy. Consensus recommendation; unable to assess using GRADE methodology. | |

| We recommend a positive diagnostic strategy as compared to a diagnostic strategy of exclusion for patients with symptoms of IBS to improve cost-effectiveness. Strong recommendation; high quality of evidence. | |

| We suggest that anorectal physiology testing be performed in patients with IBS and symptoms suggestive of a pelvic floor disorder and/or refractory constipation not responsive to standard medical therapy. Consensus recommendation; unable to assess using GRADE methodology. |

| We recommend against routine stool testing for enteric pathogens in all patients with IBS. Conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence. | |

| We recommend against routine colonoscopy in patients with IBS symptoms younger than 45 years without warning signs. Conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence. | |

| We do not recommend testing for food allergies and food sensitivities in all patients with IBS unless there are reproducible symptoms concerning for a food allergy. Consensus recommendation; unable to assess using GRADE methodology. |

Subtyping IBS1,7

Appropriate management of IBS requires accurate diagnosis of the patient’s IBS subtype. IBS subtypes are based on the predominant stool form pattern. IBS subtyping should be established when the patient is not taking medications used to treat constipation or diarrhea. The Bristol Stool Form Scale is a validated descriptor of stool form and consistency.

Adapted with permission from © 2006 Rome Foundation.

IBS-C: constipation predominant

>25% hard or lumpy (BSFS types 1 and 2)

IBS-M: mixed stool pattern

>25% hard or lumpy (BSFS types 1 and 2)

>25% loose or watery (BSFS types 6 and 7)

IBS-D: diarrhea predominant

>25% loose or watery (BSFS types 6 and 7)

Downloadable Resources for You and Your Patients

An open dialogue focused on understanding the patient’s most bothersome symptoms may help reduce treatment delays and improve treatment expectations. The resources here are designed to help start the conversation and help with patient education and treatment management.